Joshua A. Norton

Values Codes H – E – L

Joshua A. Norton was born in London in 1819

Joshua Abraham Norton was the son of John and Sara Norton, who migrated from England in 1820 to settle in Cape Town, South Africa.

News of the California Gold Rush brought Joshua A. Norton to San Francisco in 1849.

San Francisco

For a number of years, Joshua Norton operated successfully as a commission merchant and as a real estate investor.

Near the end of 1856, after a disastrous attempt to corner the rice market, Norton went bankrupt and disappeared from San Francisco.

It is said that he lost both his fortune and his “marbles.”

The Jewish Emperor

Less than three years later, he emerged to public view as Joshua Norton I, Emperor of the United States, via an announcement he placed in the San Francisco Bulletin.

That notice of the self-appointed Emperor was run on the front page, gratis, by the editor – probably due to a slow news day.

The citizens of San Francisco accepted their new “Emperor” in the “spirit” of San Francisco.

From the fall of 1859 until January 8, 1880, “Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico,” as inscribed on his headstone, was San Francisco’s most famed and beloved eccentric.

Demented but loved, he became the symbol of the tolerance of the Golden Gate city.

Emperor Norton walked the streets garbed in a blue military uniform with large gilt epaulets on his shoulders, a tall beaver hat, a knotty cane, and a sword at his belt.

He inspected new buildings and insisted that the streets be clean.

His popular figure was seen everywhere, and all deferred to him.

When Emperor Norton needed a new uniform or new pair of shoes, they were promptly provided by one of the obliging merchants.

Each Saturday morning the Emperor sat in the first row of the balcony of Congregation Emanu-El.

Proclamations

Emperor Norton regularly issued proclamations on a variety of subjects.

Perhaps his most famous was the one printed in an Oakland paper in 1869, ordering “a steel suspension bridge be constructed” across the Bay to San Francisco.

At that time, the only suspension bridges were made with rope and vines in South America.

On slow news days, various newspapers would make up their own proclamations and credit Emperor Norton.

This makes it hard for historians to determine which were really his.

Once a week, Emperor Norton visited Oakland, and was never charged for the ferry ride.

He enjoyed a “grand promenade on Broadway,” and occasionally someone would provide a horse for him to ride around town.

He had a box at the Opera and stayed in the best of hotels, careful not to overstay his welcome.

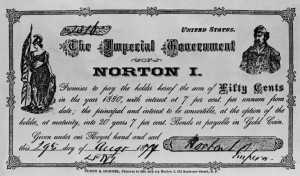

Norton Scrip

From time to time, Emperor Norton stood in need of money, and printed his own paper money in amounts of 25 and 50 cents, and $5.00.

The citizens of San Francisco, who avoided most U.S. paper money, accepted Emperor Norton’s.

Norton Scrip from 1880 read as follows:

“The Imperial Government of Norton I Promises to Pay the Holder Hereof, The Sum of Fifty Cents in the Year 1880. With Interest per Annum.”

Each one of these pieces of currency was dated and signed, “Norton I, Emperor.”

Today, Norton Scrip sells for thousands of dollars between collectors.

When Emperor Norton passed away in 1880, his funeral was arranged and conducted by the elite of San Francisco.

He was interred in the Masonic Cemetery, with thousands of mourners in attendance.

In 1934, when that cemetery was abandoned, the Emperor Norton Memorial Association was formed to rebury him in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Emperor Norton attached to the bow of the “Harbor Emperor” tourist boat, San Francisco Harbor, today

Sources

- Norton B. Stern, “Emperor Joshua A. Norton,” Western States History 41/2.

- Abraham Hoffman, “Joshua A. Norton: California’s First (and Only) Jewish Emperor and the Clampers,” Western States Jewish History 42/1.

![WS3989-^Emperor Joshua Abraham Norton ^Reburial-San Francisco,CA [1934]](http://www.jmaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/WS3989-27-C-Norton-Reburial-San-FranciscoCA-1934-1024x576.jpg)