Jewish Business Cards of Early Los Angeles and San Francisco

Early versions of the business card circulated among China’s upper class during the fifteenth century. These “visiting cards,” which typically listed credentials, were used for self-promotion and to request meetings. Servants would collect the cards from prospective visitors for review by their wealthy masters.

This custom spread to Europe by the the mid-seventeenth century. Roughly the size of modern business cards, visiting cards were used by social elites for everything from business to dating.

During the nineteenth century, the practice of handing out cards reached the middle class. Tradespeople made effective use of “trade cards,” which described their business on one side and had a map or directions on the other.

In high-class homes, silver card trays were found on hall tables. Visitors would sign “calling cards” and place them on the trays. Cards were also exchanged between new acquaintances to cement social connections.

With the growth of the middle class and the decline in social formalities, calling cards and trade cards merged into precursors of our present-day business cards.

The Jewish Museum of the American West has an extensive collection of business cards from pioneer Jews in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Many of them are old-fashioned calling cards, as seen in the examples below.

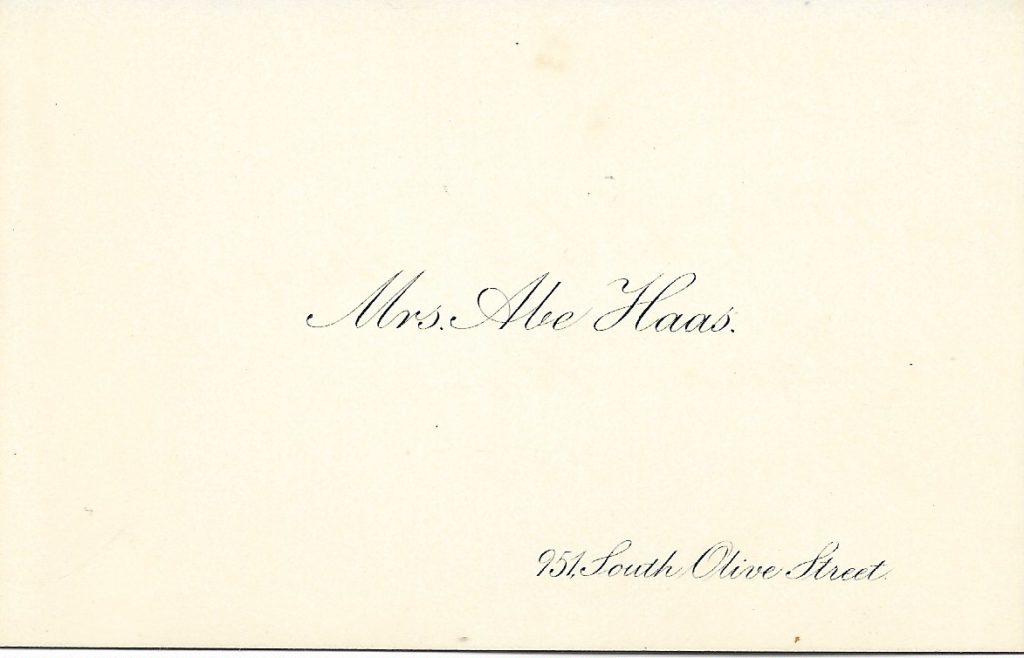

Mrs. Abe Haas

Abraham Haas was married to Fanny Koshland, the daughter of Simon Koshland — one of the leading wool merchants in San Francisco.

Haas was born in Bavaria in 1847.

Around 1867, he co-founded a Los Angeles wholesale/retail grocery store, Hellman, Hass & Co. The store sold “everything from drugs to explosives.”

Hellman, Haas & Co. was one of seven names in the first Los Angeles phone directory.

From his share of the profits, Haas launched the first flour milling and cold storage businesses in Los Angeles, along with several electricity and gas companies — forerunners of the current Southern California power companies.

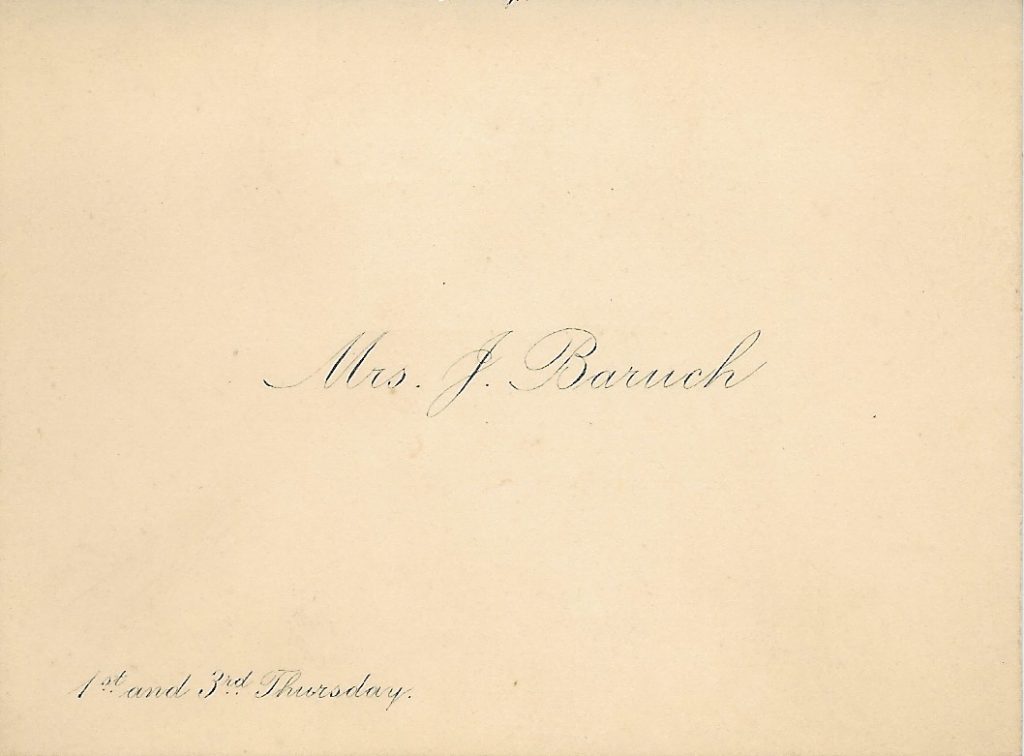

Mrs. J. Baruch

Jane Baruch was the wife of Jacob Baruch.

Along with Abraham Haas, Jacob Baruch took ownership of Hellman, Haas & Co. in the 1800’s. In 1889, they changed the company name to Haas, Baruch & Co.

By 1900, Haas, Baruch & Co. was Los Angeles’ preeminent wholesale grocer.

The company eventually morphed into today’s Smart & Final grocery chain.

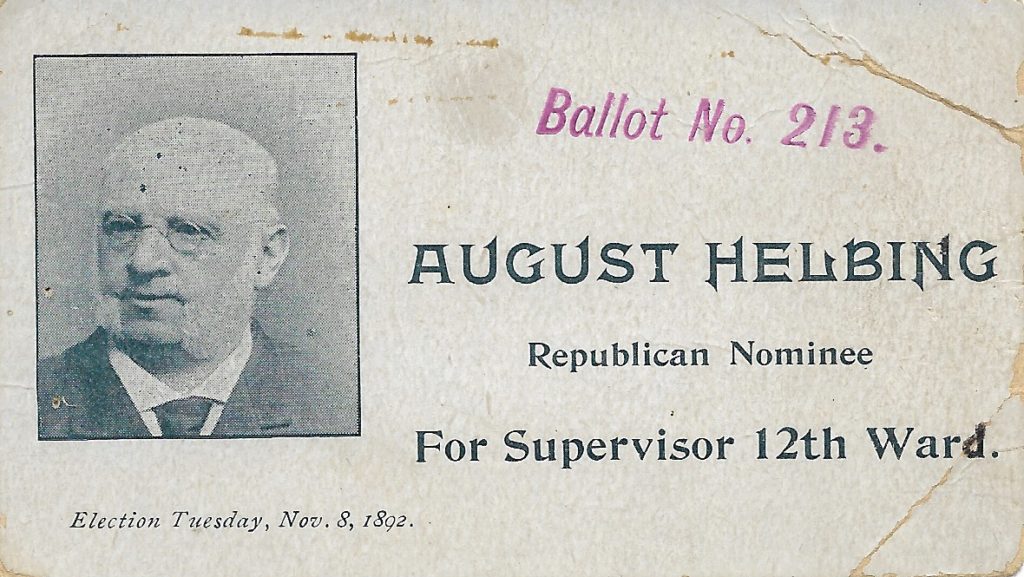

August Helbing

Bavarian-born August Helbling arrived in San Francisco in 1850, where he helped found the dry goods company of Meyer, Helbing, Strauss & Co.

The business was changed to crockery in 1860, under the name Helbing, Strauss & Co.

After a series of fires, the crockery business was reorganized as a stockbroker firm and then an insurance firm, with Helbing, Strauss, and Jacob Greenbaum as partners.

August Helbing was a founder of the Eureka Benevolent Society (today’s Jewish Family & Children’s Services of San Francisco), and was elected as the society’s first president in 1850 — the year he arrived in San Francisco.

In 1892, Helbing ran as the Republican candidate for San Francisco City Supervisor for the 12th Ward.

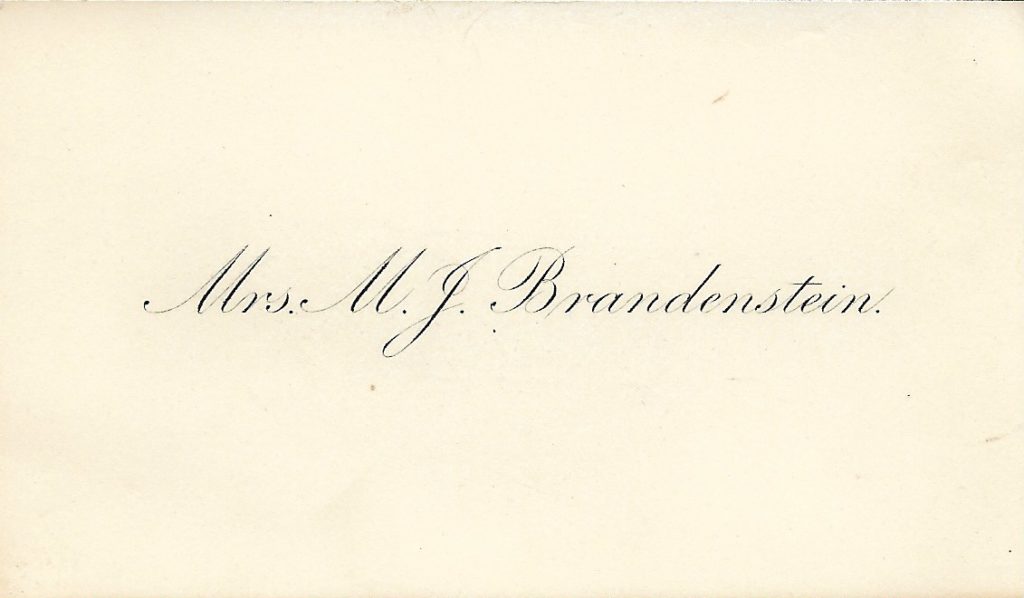

Mrs. M. J. Brandenstein

Max Joseph (M. J.) Brandenstein was born in San Francisco on February 2, 1860.

His German-born father, Joseph Brandenstein, arrived in California in 1850 and opened a wholesale leaf tobacco and cigar store in San Francisco.

Joseph Brandenstein distinguished himself as a major figure in the German and Jewish communities.

In 1881, M. J. Brandenstein started the MJB Coffee brand with assistance from his brothers Mannie, Charlie, and Eddie.

M. J. Brandenstein married Bertha Well in 1885. They had four children.

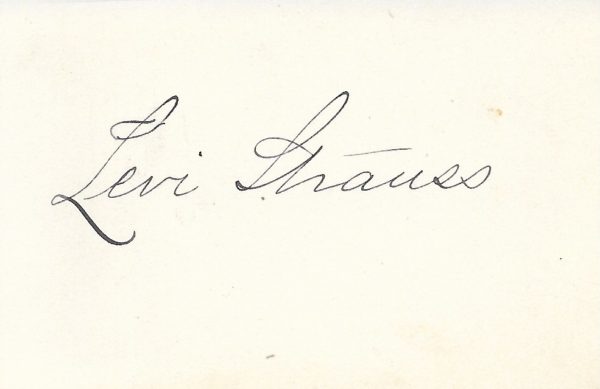

Levi Strauss

Levi Strauss was born in Bavaria in 1829.

Shortly after landing in San Francisco in the 1850’s, he began receiving shipments of merchandise from his brothers in New York.

Strauss built Levi Strauss & Co. with his partner and brother-in-law, David Stern.

Jacob Davis, a Jewish tailor in Nevada, bought fabric from Levi Strauss & Co., from which he made horse blankets, tents, and wagon covers.

A woman complained to Davis that her husband’s pockets in his work pants kept tearing. Davis affixed rivets to the pockets, thus revolutionizing work pants. U.S. Patent #139,121 was granted in 1873 to Levi Strauss & Co. and Jacob Davis.

Strauss and Stern helped fund the building of San Francisco’s Congregation Emanu-El. Strauss also supported the Pacific Hebrew Orphans’ Asylum and Home, Eureka Benevolent Society, Hebrew Board of Relief, and numerous other charities.