Frances Wisebart Jacobs

Values Codes I – E – L – P

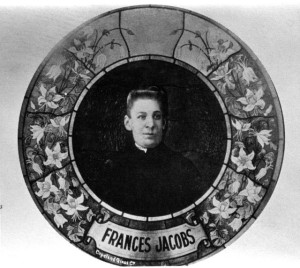

In the golden dome of Colorado’s state capital building are 16 stained glass windows, each a portrait of a prominent pioneer.

One woman was chosen for this select group –a Jewish woman — Frances Wisebart Jacobs, Colorado’s “Mother of Charities.”

Frances Wisebart was born in Herrodsburg, Kentucky in 1843, the first daughter of Leon and Rosetta Wisebart, who had come to America from Bavaria.

Wisebart attended public schools in Cincinnati, where she associated with other Jewish children, including one Abraham Jacobs, a friend of her brother, Benjamin.

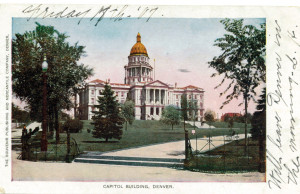

Denver, Colorado

Abraham Jacobs, who had been born in Germany in 1834, came to this country with his parents in 1843.

In 1859, Jacobs moved to the little frontier town of Denver, where he opened a clothing store and became active in politics.

Benjamin Wisebart decided to move to Denver in 1862 and became a business partner with Abraham Jacobs, and also became active in local politics.

In 1863, Jacobs returned to Cincinnati to marry 23 -year-old Frances Wisebart.

The couple came west to Central City, about 35 miles west of Denver in the mountains where Wisebart and Jacobs had opened a second store.

Two children, a son and a daughter, were born to Abraham and Frances Jacobs.

Civic

In the 1870’s, the couple moved to Denver where Frances Wisebart Jacobs became interested in being a volunteer social worker.

Frances was one of the organizers of the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society in 1872, and served a term as its President.

Recognizing that sickness and poverty were not limited to Jews, she helped organize the Denver Ladies’ Relief Society in 1874.

“The ladies new system of canvassing the city for supplies and seeking out the destitute has been a great success.”

– The Rocky Mountain News, January 20, 1878

Coal, food and soap were the prime necessities.

“It is not the auxiliary of any church or denomination or for the relief of any nationality. They have endeavored to assist all alike. No garret in the city is so inaccessible that it has not been visited. No weather is so bad that the ladies have not been out to make inquiries and then to carry comfort and aid as soon as possible.”

— The Rocky Mountain News, November 17, 1881

Frances Jacobs never seemed to mind visiting the sick and impoverished, offering her services with a keen sense of humor – perhaps a safety valve for the release of tension for the serious conditions she encountered. Her work became recognized in Jewish communities throughout the country.

In order to fund their programs, the Denver Ladies Relief Society sponsored the city’s largest ever charity ball, held at the Tabor Opera House. 400 people attended.

In the next few years, Frances Jacobs focused on creating a community association to handle all the city charities and a free kindergarten day care program for poor working mothers. Today, this is Denver’s United Way.

The 1887 charity event of the Ladies Relief Society brought together 2,000 of Denver’s leading citizens. Jacobs served as its first Vice President at that time.

During the 1880’s Denver became known as a health resort. Its clean air and sunshine were said to be a cure for tuberculosis.

Hundreds who suffered from the “White Plague” came to the city – and many were Jews from the crowded tenements of New York City.

Their plight was pitiful, and Denver’s small community had no resources to care for the influx. A sanatorium had to be build.

Meeting opposition from her normally helpful friends in the press, because they did not want to sully the reputation of the “Queen City of the Plains,” she turned to the leaders of the Jewish community.

The Jewish National Hospital Association of Colorado

Rabbi William S. Friedman, the new Rabbi of Temple Emanuel, and a few of its Trustees called for a meeting in 1889 for the purpose of building a hospital.

Early in 1890 the Jewish National Hospital Association of Colorado filed Articles of Incorporation with the State.

It proceeded to collect funds to buy land and erect its first building.

Always overworked and neglectful of her own health, and exposed to disease in the course of her work, Frances Wisebart Jacobs passed away of a cold and infection just two months after the beginning of the hospital in 1892 – at the young age of 49.

When completed, above the door of the new hospital was a large sign with the words: Frances Jacobs Hospital.

Unfortunately, an economic downturn due to the falling price of silver, dried up contributions. The building stood closed.

In 1895, Louis Anfenger became the President of the District Grand Lodge of B’nai B’rith, and at a large convention in Toledo, Ohio, told of the plight of the Denver hospital and the necessity of putting it into operation – calling it an institution “of national importance to American Jews that must be supported by the country at large.”

To be national in scope meant it must be supported by donations from all people, as well as Jewish communities around the country.

The wooden sign of “Frances Jacobs Hospital” was no longer suitable.

“While the “Frances Jacobs Hospital” will not exist in name, it will be a pleasure to know that out of her efforts has grown an institution, national in scope and dedicated to the humane and charitable work in which during her lifetime she so earnestly engaged.”

– The Rocky Mountain News, July 29, 1897

In 1900, just 16 months after the dedication of the National Jewish Hospital, the selection of the 16 pioneers to be honored by a stained glass portrait in the dome of the Capital building was announced. By unanimous approval of the selection committee, Frances Wisebart Jacobs was selected as its only woman.

“The Women of Colorado are represented by Mrs. Jacobs.” She was “the philanthropist – the doer of good deeds.”

— The Denver Republican, July 4, 1900

Source

- Marjorie Hornbein, “Frances Jacobs: Denver’s Mother of Charities,” Western States Jewish Historical Quarterly 15/2.

David Epstein is curator of this Frances Wisebart Jacobs exhibit.